‘Dark Heart’, the 2014 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art, aims to plumb the depths of the Australian psyche, investigating issues of ecology, intercultural relationships, gender and political power. It features the work of twenty-eight artists and collectives practising across photography, painting, sculpture, installation and film. During the opening weekend, Lucy Rees spoke with Patricia Piccinini, whose Skywhale, 2013–, flies over the Botanic Gardens of Adelaide to mark the beginning of the event; Ben Quilty, represented in the biennial with an epic work titled The island, 2013; and Richard Lewer, who debuts the raw and confronting Worse luck … I am still here, 2013.

Patricia Piccinini

Lucy Rees: Your work has evoked a strong reaction from children in Adelaide.

Patricia Piccinini: A child came up to me and asked ‘am I dreaming?’ I had a similar experience coming to the Art Gallery of South Australia when I was a child. My mum had done a workshop here and it stayed with me. It’s an important formative time. Skywhale is not a work for children though, it works on another level, but I think it’s a great response. For them, they don’t see the mutation – they accept her for what she is. A walrus is new to children, and this is just another new thing. As we get older, our world gets smaller and we start to doubt and question. We are really suspicious of difference. I am asking ‘could this be a creature that is engineered and could this be a good thing?’

Thinking is a social process. I talk to everyone from children to anthropologists and philosophers. I try my ideas out on people and they talk back to you. That’s how ideas get formed. This is about the world around us. In one hundred years time people will look back and think ‘these people were really worried about the environment, they were looking at things to do with global warming, and this is why they were making work about these issues’. The way we look at nineteenth-century English social realism and appreciate the working classes of the emerging industrial revolution.

LR: What does ‘Dark Heart’ mean to you?

PP: I don’t think ‘Dark Heart’ has to be malevolent. It conveys a sense of depth. There is a sense of questioning turmoil.

Skywhale is ambiguous. I think she is beautiful, but a lot of people think she is grotesque. You are drawn in and repelled at the same time, and it has to have that dynamic. My work has a certain element of abject mutation, uncertainty and darkness. Even she is dark – I mean she has ten breasts.

LR: What will happen to her at the end of her life?

PP: She has a lifespan, and she will die. She won’t be safe to fly or tether. I suppose the nylon will just wear away. It’s a long way away; she is at the beginning. You don’t think about your child’s death when you have just given birth. It’s a joyful time.

Ben Quilty

LR: How were you approached to participate in the biennial?

Ben Quilty: I wanted to make a massive work so as soon as Nick Mitzevich invited me I said yes straight away and began to make the work. The island was made in direct response. I used the diagnostic tool of Rorschach blots – something designed to extract and evaluate the dark and unconscious elements of our personality.

LR: Tell us about the process behind The island.

BQ: The original image is a nineteenth-century painting by Haughton Forrest titled Gordon River, Tasmania. I’d never seen Forrest’s work before until I came across it on the front of an ANZ book. I then researched a whole lot of his work. This painting was made from a black-and-white photograph; he imbued the colour. There is that interesting thing that he was imagining the landscapes. They are so dramatic. They are dark, big, gloomy paintings and he was making them during some of the most ominous massacres in Tasmania. Forrest was recording history but missing the human story.

I got a high-res copy off the ANZ bank, blew it up, stretched it out, then hand drew it and the painting was done very quickly. Everything that you can see I got down in five days. I worked night and day, and that’s why I don’t do paintings like this often because my wife almost left me and I was pretty close to madness. Half way through it there is a point where you know this is going to work, but I always worry ‘is this just going to be a waste of thousands and thousands of dollars of materials?’

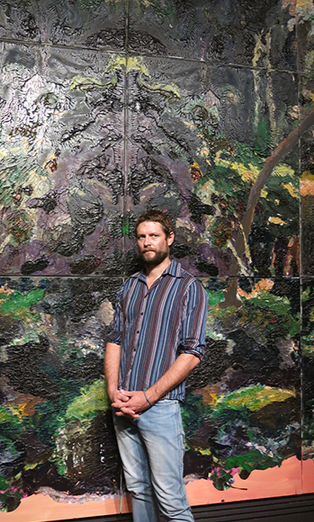

Richard Lewer

LR: How did Worse luck … I am still here come about?

Richard Lewer: Nick Mitzevich had seen my work with Tony Garifalakis, who is also in the show, in particular my animation The sound of your own breathing, 2010, at Hugo Michell Gallery. Nick is quite interested in my extreme storytelling animations, and I wanted to make a new animation drawn from Western Australia, where I am living now. The work is ‘collected’ from my local community in Fremantle, but it didn’t come about from the curatorial premise of ‘Dark Heart’ necessarily.

I experiment the hell out of my animations. I thought ‘how could I do this myself?’ I used a lo-fi projector. I like the raw intimacy. Someone told me the other day that it looks like I did it over the weekend in my back garage. That is exactly what I want! I like that anyone could do it. It’s not the technology that wows you, it’s the story.

LR: Tell us about Herbert Bernard Erickson.

RL: Worse luck … I am still here is a self-narrated animation created in response to a news story about a Perth-based pensioner, Herbert Bernard Erickson, who survived a failed suicide pact with his wife Julie in 2012. He tried to kill himself at the same time as his wife and their dogs but it didn’t work. He was charged with murder, and then successfully drowned himself a few weeks later at the beach. He didn’t want to live without the love of his life.

In Worse luck … I am still here I am the narrator. I scan the papers every day. I collect extremes. I read about this in 2011 and I thought what a tragic story; I needed to tell it. I started thinking about bravery: could I ever be brave enough to do this suicide pact? I started to consider my own mortality. That was one of the reasons we moved to Fremantle – I was really sick. Up until then I thought I was seventeen years old, impenetrable.

LR: How do you feel telling such a personal story?

RL: I document. I don’t want to sensationalise. I want to tell the story the best way I can. So many people have come up to me and told me this work connects to them. It’s got death, love, animal cruelty – it’s a highly sensitive topic.

LR: You have an extraordinary attention to detail. Do you storyboard or are you just highly imaginative?

RL: I don’t storyboard. It’s totally organic. I got professionals in but it didn’t work, I just experiment and imagine. Nick had no idea what he would get with this work.

2014 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Dark Heart, Art Gallery of South Australia, 1 March – 11 May 2014.

This article was published by Art & Australia.