LR: A lot of the time your work is thematized, either in curated group shows or when it’s written about in art journals. It can be pigeonholed. If there was a myth to be dispelled about your practice, or something you feel has been too focused on, what would it be?

WM: I think people get lazy. They read what has already been written and base their writing on other people. And it spirals. I follow certain trains of thought. And I can say: “That came from that article, which came from that article…” Even when I go to a museum and see a show I think I should try to be open and fresh about it. But I think there are some things that haven’t been focused on enough, or brought up with my work. Until recently people were still confusing me for American. So I think one of the things I have always wanted is to be understood in the realm of contemporary African art.

LR: So you feel very strongly rooted to your African heritage?

WM: I really do. I lived there until I was twenty, my formative years. It’s hard to ever get rid of those influences and that training. And the beauty of being born there, you can’t undo it. I think some things that I place in the work have so much to do with Kenya. America is not as interested in contemporary Africa as I would like it to be.

LR: Would you say the same for the rest of the world, or America specifically?

WM: I think Europe has an interesting, problematic and long relationship with Africa. The geographical proximity, the colonial history. There are a lot of Africans living in Europe. I have found that there are more Europeans willing to go there, who are more confident about saying things without looking over their shoulder and worrying: “Am I being stereotypical?" Sometimes I do think that people extrapolate feminism a lot. I am a big feminist, but I am not coming from the Western understanding of feminism. It’s not an American feminism. The protests I follow by African women are very different from the protests that happen in the US or Europe.

LR: Let’s talk about this idea of multiple feminisms.

WM: I was in a show in 2007 at the Brooklyn Museum called “Global Feminisms.” It had so many problems that were interesting because they were inherent in the idea of feminism being plural. There were all these women from all over the world, but the discussion between the feminisms was really difficult to have. I mean, people’s feminism, or rather, people’s interest in women’s empowerment, comes from totally different places. It’s not about art anymore. It’s about life and politics.

LR: Interesting that the concept of feminism is a Western construct — it doesn’t actually exist in most of the world.

WM: Yes, yet there is a long history in these countries of the strength of the female, and the female body, that is undeniably a feminist space. These are some of the areas I’d like more focus on.

LR: Your largest retrospective to date is currently on at the MCA. Let’s talk about some of the works.

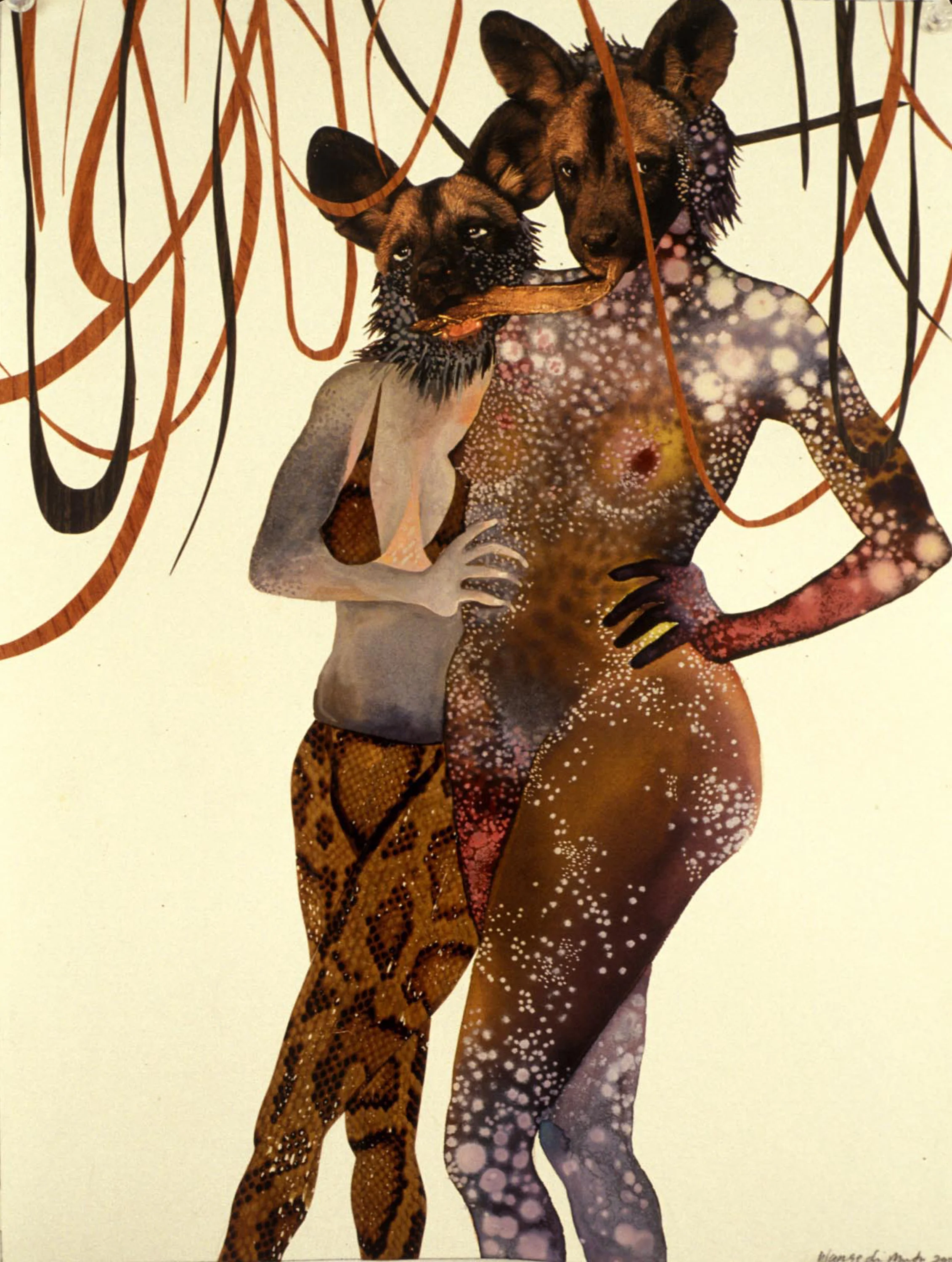

WM: The curator, Rachel Kent, knew of all these works, and I was astounded that she wanted to transport so many big installations to Australia. All my works are like babies, they’re my children; it’s hard to pick out favourites. Although some have been problem children! Exhuming Gluttony: Another Requiem (2006) was a very expensive and very elaborate installation with a lot of dense issues, but ultimately I wanted to create a feast, a communing of people and minds and viewers. Something has gone wrong, there is a tragedy or unfolding of evil. It is a confluence of issues to do with war, with consumption and waste, wealth, America. Exhuming Gluttony: Another Requiem (2006) took a lot longer, it was much more complicated in terms of how many people assisted me to make it. Then there’s of course my little Intertwined (2008) piece where I combine two bodies from a fashion magazine in this erotic sexy pose. When I made the decision to put the hunting dog heads on them it was such a milestone. A moment when I decided to make African women like animals. I wanted to pay homage to mythology and the use of animals as a way of understanding human behaviour, but also how women are depicted like animals. All these things are intertwined into the one piece. There are two energies — one is much stronger and the other is coyer. It was magnificent how it just worked. Mud Fountain (2010) is a video work where I am actually posed as a woman in a cell. Actually I’ve been thinking how I use Catholicism and the Catholic Church as a major form of inspiration.