Sydney, Australia

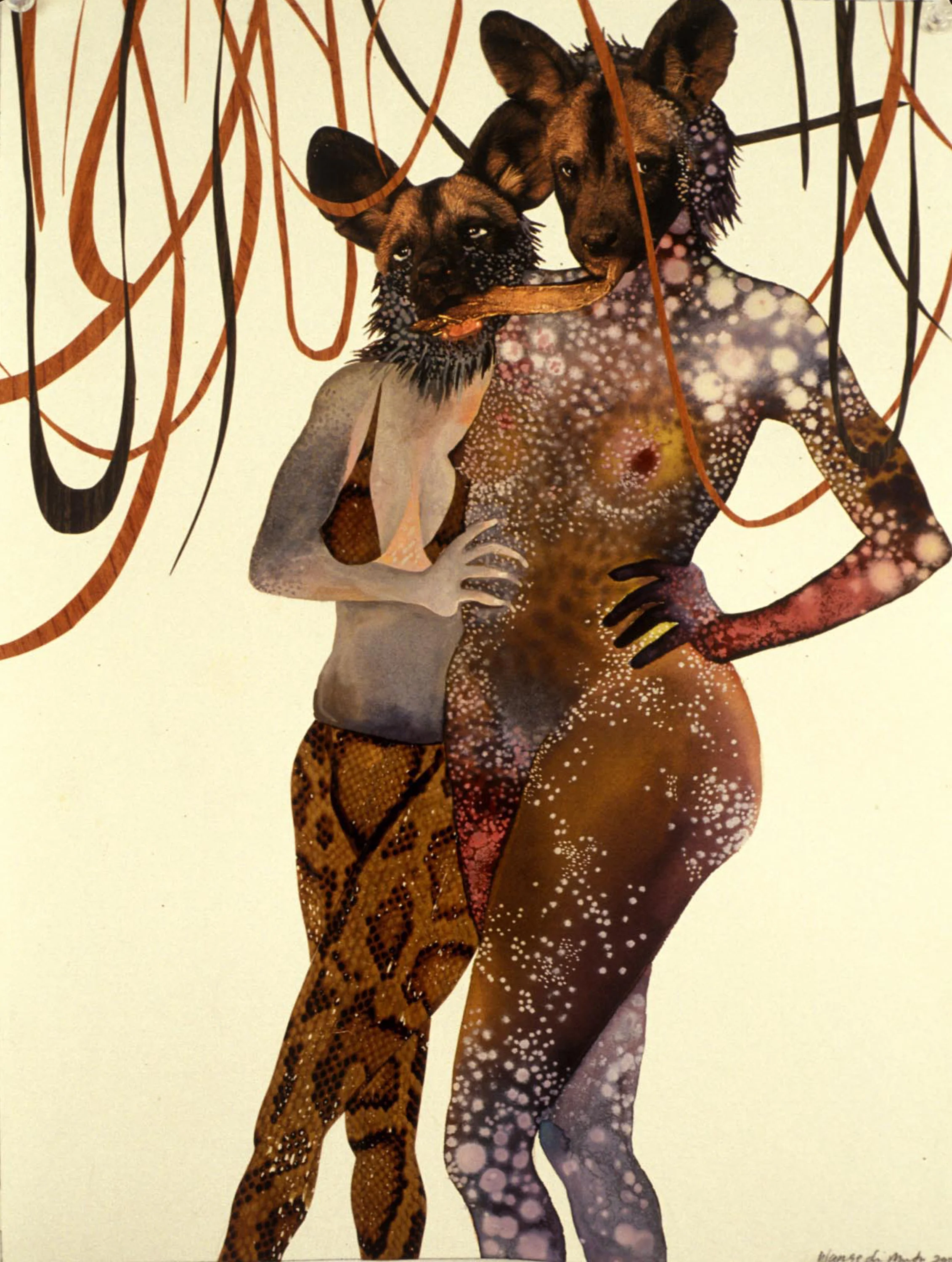

Interwined, 2003

An interview with Kenyan-born, Brooklyn-based artist Wangechi Mutu. Her sculptures, works on paper, installations, and videos explore gender, race, and sexual identity using collage and assemblage strategies that create provocative juxtapositions of the female body. 'Wangechi Mutu', curated by Rachel Kent, is on at the Museum of Contemporary Art Sydney from 23 May - 14 August 2013.

Lucy Rees: How did you first come to art?

Wangechi Mutu: I was always a visual person. I’m not really sure how I came to it. My earliest memory is drawing. Drawing until I ran out of paper. Something I would do without being asked to. I think it was my blessing and curse. It was given to me.

LR: And do you still draw?

WM: I love it. For me it’s the most genuine part of my practice. It’s the most intimate because I don’t draw for anyone but myself. I draw and sketch everything before making it. I love the quality and flow of lines in other peoples’ work. It is something I always respond to. I have a lot of sketchbooks filled with ideas. Some of my major works have started as a small sketch in one of these books. I always say to people who can’t do art that you just didn’t have a good teacher.

LR: You seem to have moved away from collage in recent years and have been focused on creating these larger all-consuming installations. Have you exhausted collage for the moment?

WM: I haven’t exactly moved on from collage but I have been doing other things, that’s true. I have just finished a collage on linoleum series titled “Girl Specimens.” It is a new body of work, thinking about the body as collected specimen. Knowledge, like science, natural science, progresses by cutting things up or even killing things in order to study them, which is such a bizarre thing. It’s a fascination for me, but also a problem. How we consider what we learn. I was looking at a lot of books of paleontological specimens and I came across these old, strange crustaceans. I loved the way they were arranged in the book formally, but also how similar some of these animals were to body parts. So, I am still making collage and I am using a new surface — linoleum. I used to use Mylar, but I was finding it limiting. It’s a tough material but it is thin so you can’t stick too much on it. So now the works are collage, sculpture, video and installation all in one.

LR: Your use of difference mediums seems to integrate seamlessly. I mean, even in your sculptures and installations there are elements of cutting, layering, building…

WM: Yes, it’s definitely the way I think. I don’t naturally segregate them. You know, it’s funny; I get invited to do these artist talks at painting schools. Because a lot of my work is 2-D, I suppose the painting departments think of me. But I actually studied sculpture. I kind of have this weird, ambidextrous, upside-down approach to these things. I naturally combine them.

LR: Is there an angle we are supposed to read your works from?

WM: I don’t think so. That would be such an amazing thing to be able to prepare people and decide how everyone should look at something. Part of what I am saying with this interest and ability of mine to combine things is also about not treating them in a hierarchal manner. For me, my work is more about the viewer. I want people to see them how they want. Some people see women, and that’s it. And then there are other people who see that the women are cut up, or broken, or question if they are really women or animals. If you are not interested in the issues, such as the objectification of women’s bodies, then this part won’t strike you. I think people are willing to see what they are ready to see. That said, I try to infiltrate the subconscious. I try to get far enough, so that if you remember the work a few months or years from now you might say, wait a minute… that is maybe what is going on.

LR: I’d agree that they have that ability. While some of your works have a more obvious or explicit message, such as your pin-up girls from The Ark Collection (2006), with others you’re not really sure what is happening. But you’re aware you are looking at something powerful and confrontational.

WM: Right. That’s my method. I am not didactic in that way. They are opinions on history or politics or social issues. They are my opinions and I want to transmit them, communicate then or even convince people that there might be some truth to them. But I just don’t believe in banging people over the head. I also really love visually interesting seductive things. I like to draw people in to a difficult message to be accepted. You can put a little pill in there. I think there are also many creatures and animals that act in this way. They draw you in, and then they bite you, or poison you or engulf you. I admire what nature does when it tries to bring you hither.

LR: A lot of the time your work is thematized, either in curated group shows or when it’s written about in art journals. It can be pigeonholed. If there was a myth to be dispelled about your practice, or something you feel has been too focused on, what would it be?

WM: I think people get lazy. They read what has already been written and base their writing on other people. And it spirals. I follow certain trains of thought. And I can say: “That came from that article, which came from that article…” Even when I go to a museum and see a show I think I should try to be open and fresh about it. But I think there are some things that haven’t been focused on enough, or brought up with my work. Until recently people were still confusing me for American. So I think one of the things I have always wanted is to be understood in the realm of contemporary African art.

LR: So you feel very strongly rooted to your African heritage?

WM: I really do. I lived there until I was twenty, my formative years. It’s hard to ever get rid of those influences and that training. And the beauty of being born there, you can’t undo it. I think some things that I place in the work have so much to do with Kenya. America is not as interested in contemporary Africa as I would like it to be.

LR: Would you say the same for the rest of the world, or America specifically?

WM: I think Europe has an interesting, problematic and long relationship with Africa. The geographical proximity, the colonial history. There are a lot of Africans living in Europe. I have found that there are more Europeans willing to go there, who are more confident about saying things without looking over their shoulder and worrying: “Am I being stereotypical?" Sometimes I do think that people extrapolate feminism a lot. I am a big feminist, but I am not coming from the Western understanding of feminism. It’s not an American feminism. The protests I follow by African women are very different from the protests that happen in the US or Europe.

LR: Let’s talk about this idea of multiple feminisms.

WM: I was in a show in 2007 at the Brooklyn Museum called “Global Feminisms.” It had so many problems that were interesting because they were inherent in the idea of feminism being plural. There were all these women from all over the world, but the discussion between the feminisms was really difficult to have. I mean, people’s feminism, or rather, people’s interest in women’s empowerment, comes from totally different places. It’s not about art anymore. It’s about life and politics.

LR: Interesting that the concept of feminism is a Western construct — it doesn’t actually exist in most of the world.

WM: Yes, yet there is a long history in these countries of the strength of the female, and the female body, that is undeniably a feminist space. These are some of the areas I’d like more focus on.

LR: Your largest retrospective to date is currently on at the MCA. Let’s talk about some of the works.

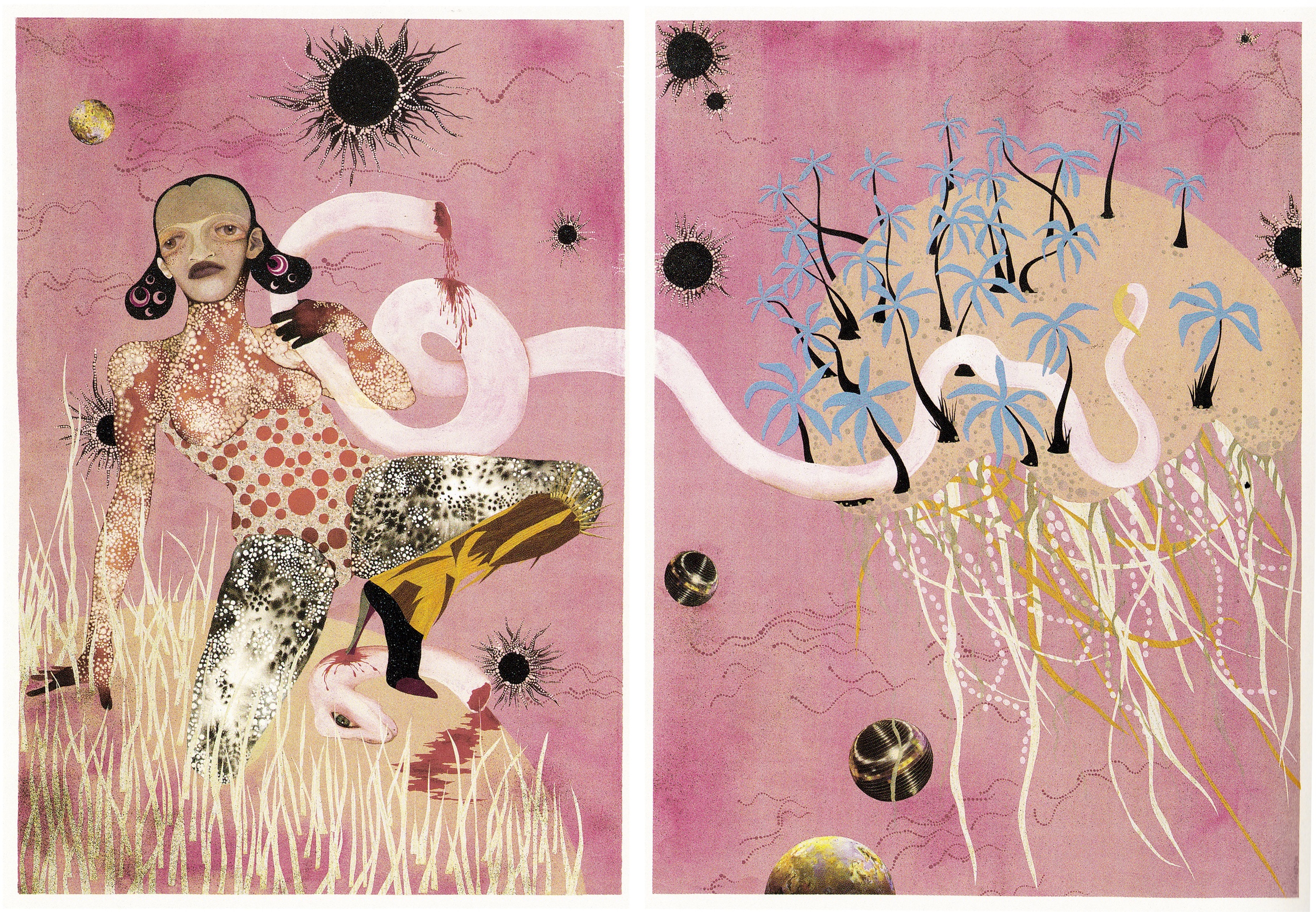

WM: The curator, Rachel Kent, knew of all these works, and I was astounded that she wanted to transport so many big installations to Australia. All my works are like babies, they’re my children; it’s hard to pick out favourites. Although some have been problem children! Exhuming Gluttony: Another Requiem (2006) was a very expensive and very elaborate installation with a lot of dense issues, but ultimately I wanted to create a feast, a communing of people and minds and viewers. Something has gone wrong, there is a tragedy or unfolding of evil. It is a confluence of issues to do with war, with consumption and waste, wealth, America. Exhuming Gluttony: Another Requiem (2006) took a lot longer, it was much more complicated in terms of how many people assisted me to make it. Then there’s of course my little Intertwined (2008) piece where I combine two bodies from a fashion magazine in this erotic sexy pose. When I made the decision to put the hunting dog heads on them it was such a milestone. A moment when I decided to make African women like animals. I wanted to pay homage to mythology and the use of animals as a way of understanding human behaviour, but also how women are depicted like animals. All these things are intertwined into the one piece. There are two energies — one is much stronger and the other is coyer. It was magnificent how it just worked. Mud Fountain (2010) is a video work where I am actually posed as a woman in a cell. Actually I’ve been thinking how I use Catholicism and the Catholic Church as a major form of inspiration.

LR: You were educated at a strict Catholic school, weren’t you?

WM: For a long time, twelve years! Catholicism is so rigid and really deeply affects you. It really gets into every little crevice.

LR: And the visual imagery of the religious and biblical stories, you can see those elements of sacrifice, transformation, etc. in many of your works. From Metha (2010) with the bottles of milk and wine, to Mud Fountain.

WM: A suffering body in the middle of the cell. The notion of suffering and bloodletting. It is ancient, pre-Christian. There is something primitive about religious imagery. It reaches back to our oldest ancestors. This notion that if you kill an animal or a person and offer its blood then the gods will be kind to you. I believe it is still there. Bride killings, war, offering animals. Mud Fountain is bringing the eye to the center of the room, to the offering.

LR: Where do you get your inspiration? You emit a curiosity about the world.

WM: I think a lot of it is within me. And I have attention deficit disorder [laughs]. I did travel a lot before I got to the US, and then I became stationary mainly because of these issues of immigration and also at times not being able to afford it. I traveled in the work, I traveled in a fantasy…

LR: And that’s the name of your show at the Nasher Museum?

WM: Yes. We tried so hard to find an appropriate name. Trevor, the curator, who knows me really well, told me about this show called “Fantastic Journey,” about this group of kids who get lost in a parallel universe and can’t seem to find their way home. It had a Wizard of Oz–like connotation — I am trying to get back home. It references the way I think, the way I go wandering off into my imagination, and it goes into my collages. The End of Eating Everything is a new 8-min video where I actually animated the way I think, my process. So that was a collage come to life. And in it, there is this female multi-cellular crazy thing traveling. She is travelling with no sense of where she is coming from and where she is going.